Reproduced from World Bank Blogs.

Article by Gerald Ollivier, Prerna Mehta, Abhishek Behera and Alina Burlacu

This blog is part of “Let’s talk about Streets for Life” – a blog series on Transit-Oriented Development and Road Safety.

Previously in its blog series, World Bank flagged the need to embed road safety systematically in a Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) project within a five step TOD framework. Today, we will be focusing on the assessing and enabling steps of the framework.

Every year, 1.35 million people lose their lives while driving, cycling, or walking on the road. Another 50 million are seriously injured, and many are left permanently disabled as a result. Most of these deaths and injuries from road crashes are of the working age population, which negatively impacts both the economy and the demography of the region.

In the short term, adjustments to infrastructure are required to manage vehicle speed and ensure safe interactions between vehicles and people. How do cities support TOD and become ready for implementing it? Below are three steps for assessing and enabling road safety in TOD:

- including socio-economic conditions, urban characteristics, transportation system and network, travel and overall road crash data, job opportunities and economic growth, etc. This allows informed planning and design decisions placing safety considerations within the development and the city at large.

- Accordingly, a detailed road crash data analysis becomes critical in identifying road safety related challenges in the area in question. This analysis helps to determine the priorities of the intended TOD project and develop an approach to address road safety aspects in that specific location. Road crash data needs to be analyzed along with social, physical infrastructure, and institutional assessment data:

- The juxtaposition with social assessment helps ascertain if the impact is felt disproportionately by certain demographics – racial and/or religious minorities, women, children, senior citizens, or in low-income neighborhoods of a city. This comparison helps in formulating targeted interventions for TOD plans. For example, women have 47% higher risk of serious injury in a car crash than men, and a five times higher risk of whiplash injury.

Women crossing busy road in Accra, Ghana. Photo Credit: Daniel Silva Yoshisato/World Bank

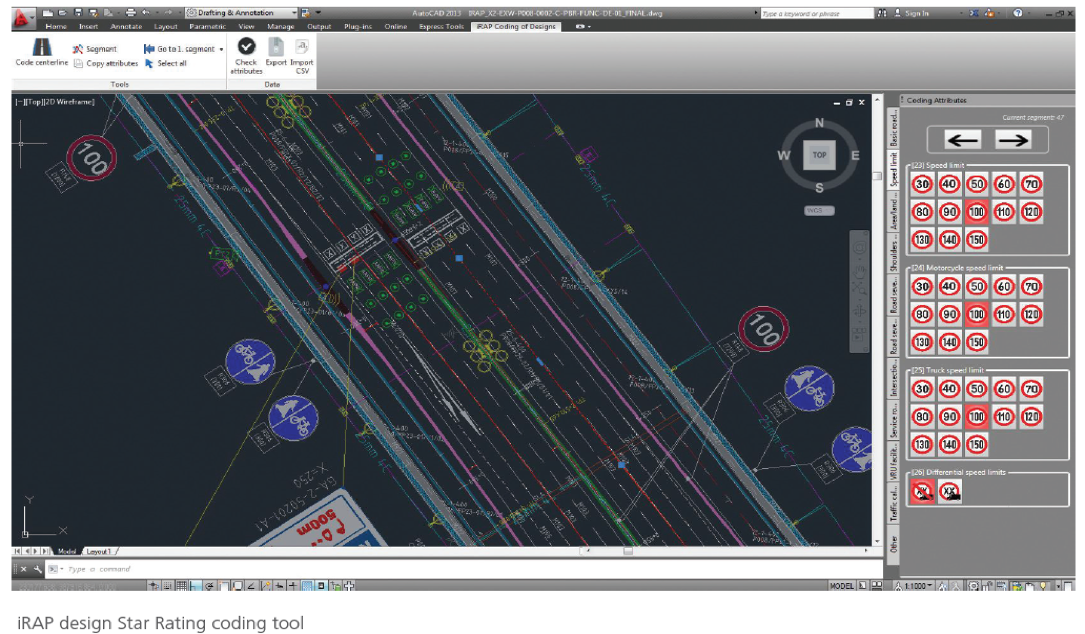

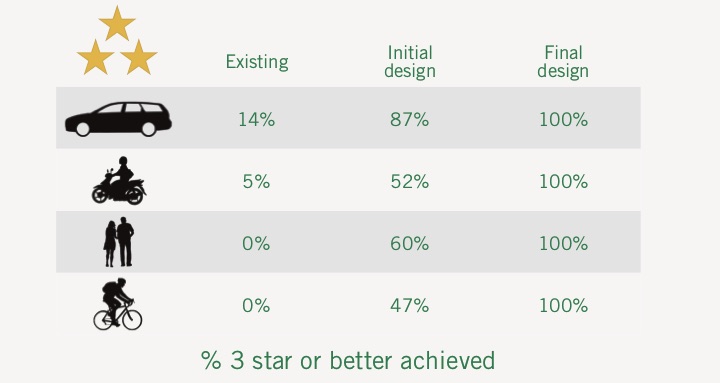

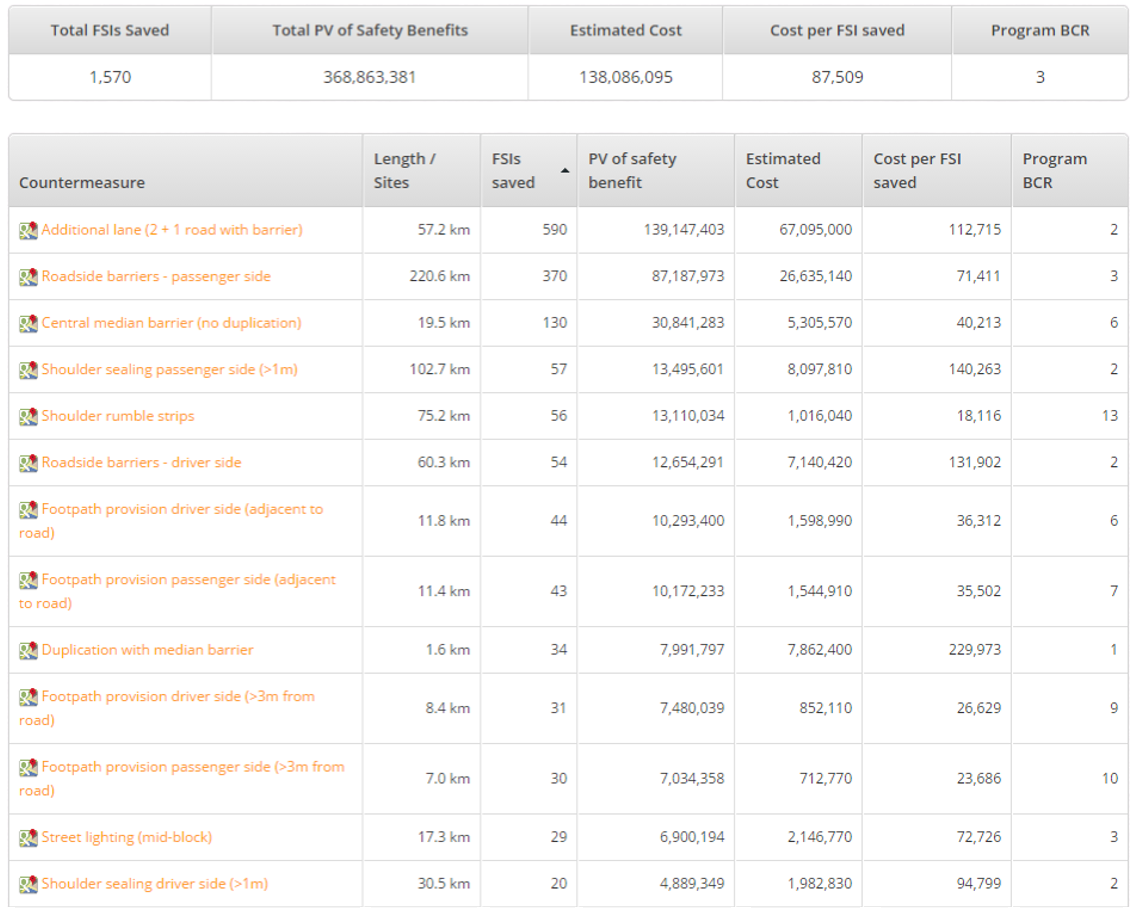

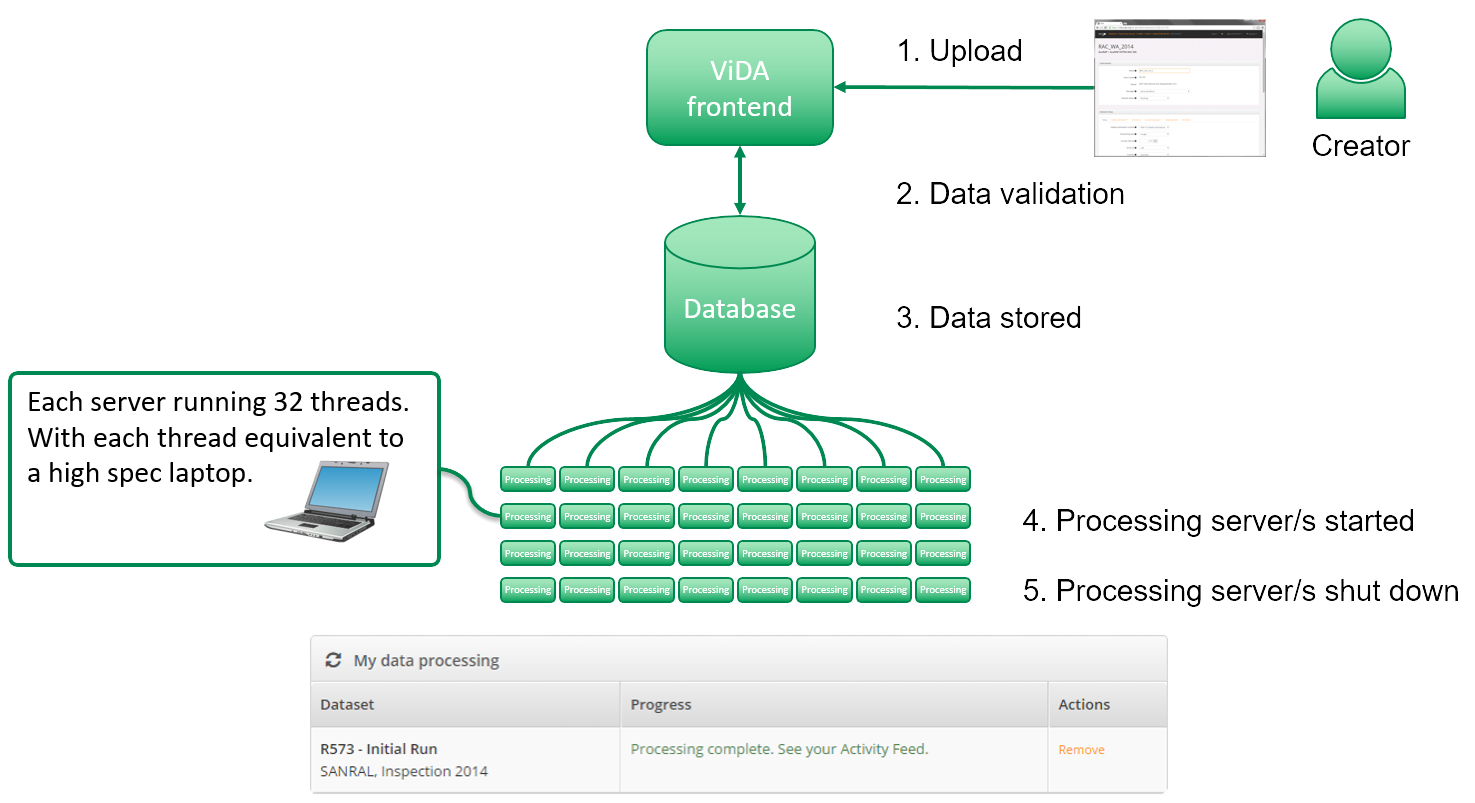

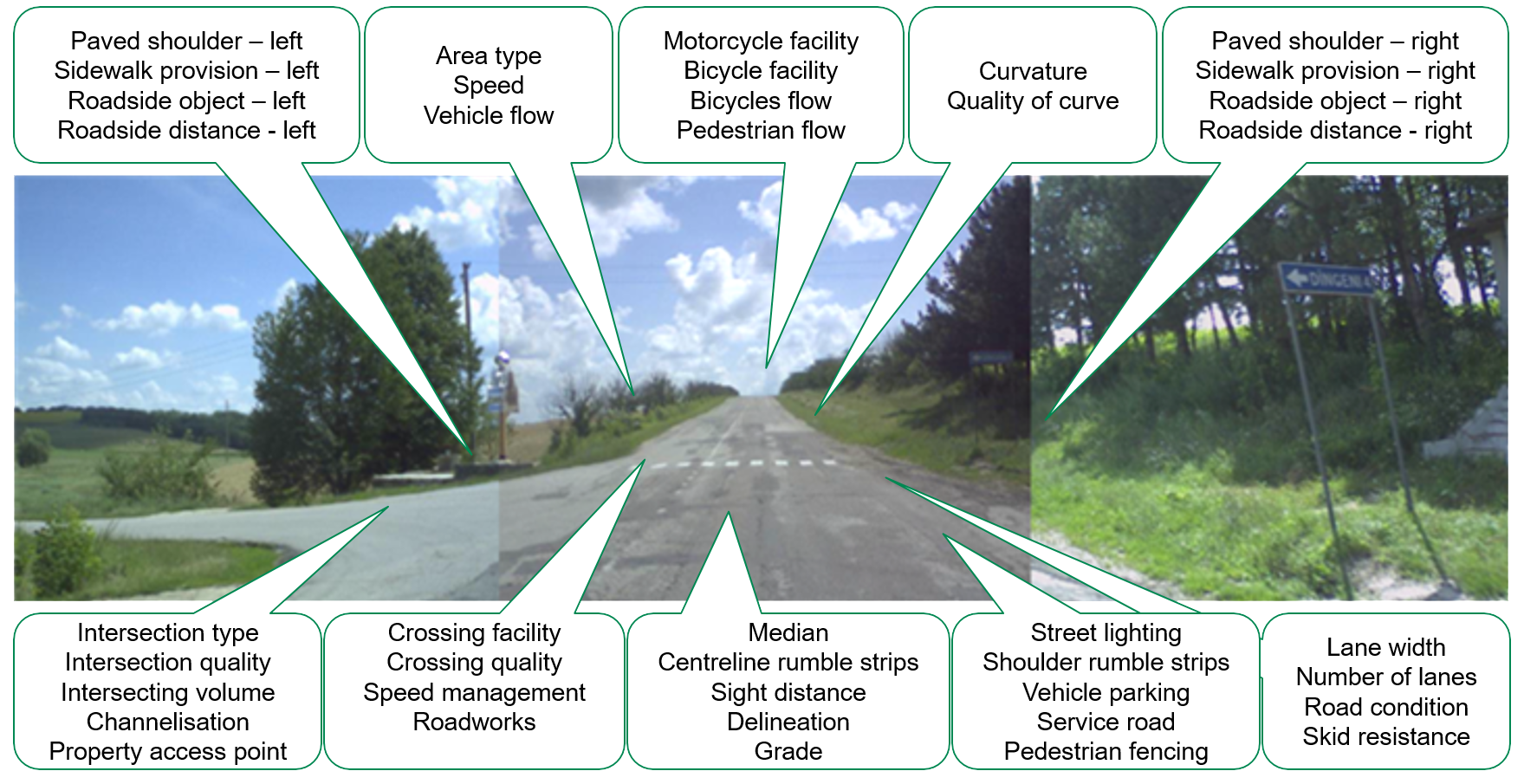

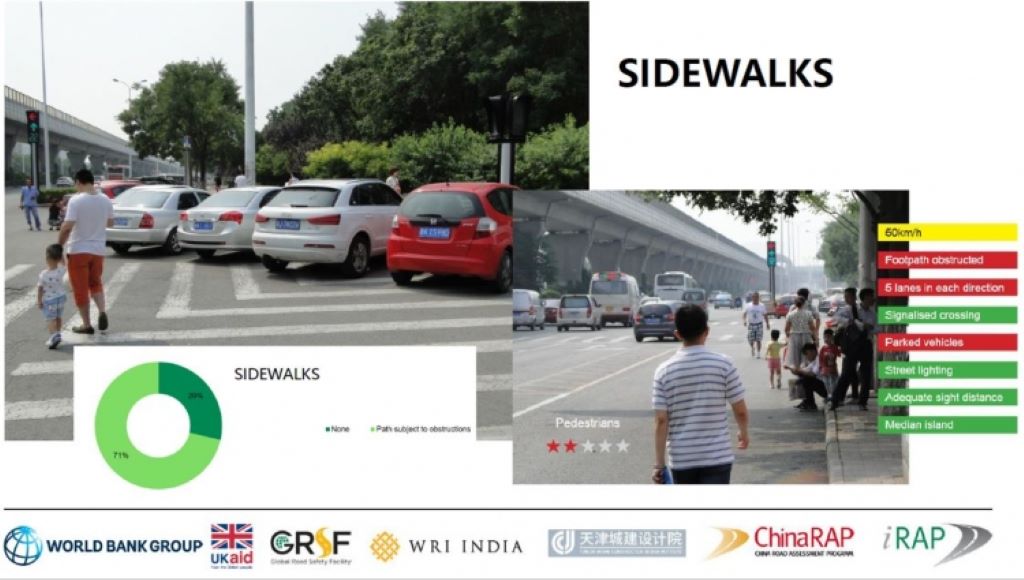

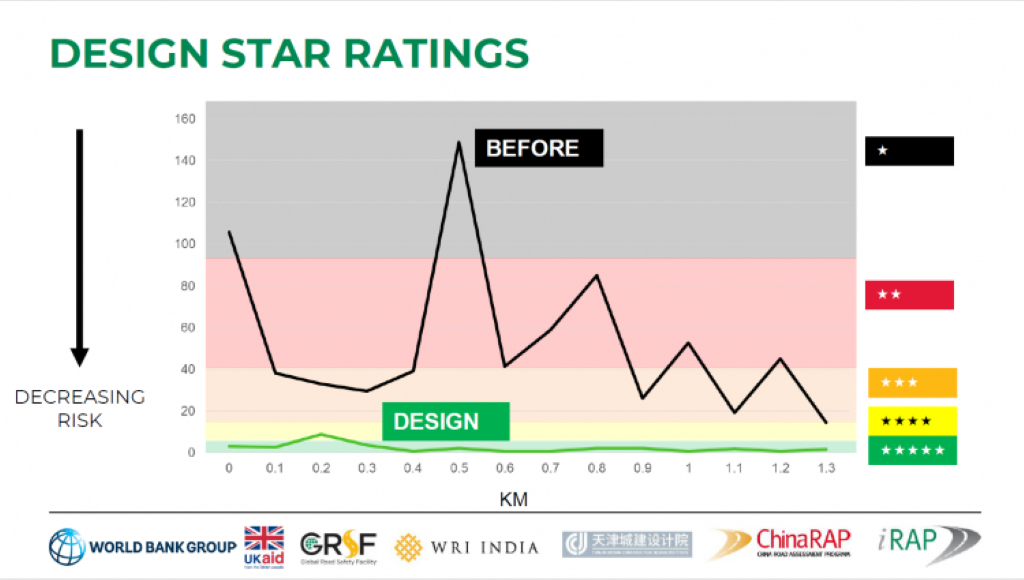

- When analyzed along with physical infrastructure assessment, the crash data assessment can determine conditions that could have led to the crash or were factors in causing a crash. These may include infrastructure fostering car speed, lack of continuous sidewalks, marked and separated cycle lanes, and the poor actual physical conditions or state of these facilities. A rating of facilities for different types of users using a methodology, like iRAP, enables a prioritization of interventions to enhance road safety characteristics for each type of users. Such approach informs necessary capital improvement projects and maintenance plans in the TOD area. An example of such approach is shown in the Tianjin Urban Transport Improvement Project, where streets and conditions before interventions were analyzed systematically with a rating to inform interventions.

Assessing pedestrian street safety under Tianjin Urban Transport Project | Photo Credit: ChinaRAP

Assessing pedestrian street safety along a corridor in a TOD zone under Tianjin Urban Transport Project before and after intervention | Photo Credit: ChinaRAP

- This includes aspects like the approach to parking and speed enforcement or the integration of safe design practices in street guidelines. The World Bank’s Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF) elaborated guidelines for undertaking a Road Safety Management Capacity Review, which can be applied to a TOD project.

- Institutional gaps that are identified through the assessment processes need to be addressed to create an enabling environment that supports creation of a safe TOD. This can be achieved through the following:

- Develop the organizational setup and capacity of the TOD implementing agency in executing a safe TOD project. Knowledge or experience gaps may be overcome through hiring of specialists, such as engineers with experience in safe traffic engineering, road safety experts, urban planners with experience in transportation and land use planning and street design, etc.

- Adjust street design guidelines to reflect a different approach to sharing street space among users, beyond a single TOD project. TOD areas provide strong opportunities to apply such concepts as shown in the picture below from Tianjin.

Enhancing pedestrian and cycle design along a corridor in a TOD zone under Tianjin Urban Transport Project before and after intervention | Photo Credit: Tianjin Urban Construction Design Institute

- Engage Stakeholders. Innovative engagement strategies have been developed through the years depending on the type of engagement. It may be carried out with a smaller focus group of representatives from different stakeholders’ groups, staff members from various departments of a local or state government, political and institutional leadership, or with the public. This not only helps in creating awareness about the TOD plan and need for road safety, but also helps in understanding the challenges faced by these groups and their concerns, leading to an informed decision-making process.

Key resources to drive action

- The updated TOD Toolkit, developed with funding support from UK Aid through GRSF, incorporates these recent updates related to road safety.

- The webinar series “Integration of Road Safety Considerations in TOD Projects” described how to systematically integrate road safety in planning, designing, implementing, and financing of TOD programs, and was built on the new World Bank/WRI India note called Good Practice Note: Integration of Road Safety Considerations in Transit-Oriented Development projects.